Why use a Cluster?

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

Why would I be interested in High Performance Computing (HPC)?

What can I expect to learn from this course?

Objectives

Describe what an HPC system is

Identify how an HPC system could benefit you.

I’ve Never Used a Server, Have I?

Take a minute and think about which of your daily interactions with a computer may require a remote server or even cluster to provide you with results.

Some Ideas

- Checking email: your computer (possibly in your pocket) contacts a remote machine, authenticates, and downloads a list of new messages; it also uploads changes to message status, such as whether you read, marked as junk, or deleted the message. Since yours is not the only account, the mail server is probably one of many in a data center.

- Searching for a phrase online involves comparing your search term against a massive database of all known sites, looking for matches. This “query” operation can be straightforward, but building that database is a monumental task! Servers are involved at every step.

- Searching for directions on a mapping website involves connecting your (A) starting and (B) end points by traversing a graph in search of the “shortest” path by distance, time, expense, or another metric. Converting a map into the right form is relatively simple, but calculating all the possible routes between A and B is expensive.

Checking email could be serial: your machine connects to one server and exchanges data. Searching by querying the database for your search term (or endpoints) could also be serial, in that one machine receives your query and returns the result. However, assembling and storing the full database is far beyond the capability of any one machine. Therefore, these functions are served in parallel by a large, “hyperscale” collection of servers working together.

Key Points

High Performance Computing (HPC) typically involves connecting to very large computing systems elsewhere in the world.

These other systems can be used to do work that would either be impossible or much slower on smaller systems.

HPC resources are shared by multiple users.

The standard method of interacting with such systems is via a command line interface.

Connecting to a remote HPC system

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How do I log in to a remote HPC system?

Objectives

Configure secure access to a remote HPC system.

Connect to a remote HPC system.

Logging onto Baskerville

For instructions specific to logging in to Baskerville, click here. Baskerville requires Two Factor Authentication (2FA) and is set up the first time you login to the cluster - please see details here.

Secure Connections

The first step in using a cluster is to establish a connection from our laptop to the cluster. When we are sitting at a computer (or standing, or holding it in our hands or on our wrists), we have come to expect a visual display with icons, widgets, and perhaps some windows or applications: a graphical user interface, or GUI. Since computer clusters are remote resources that we connect to over slow or intermittent interfaces (WiFi and VPNs especially), it is more practical to use a command-line interface, or CLI, to send commands as plain-text. If a command returns output, it is printed as plain text as well. The commands we run today will not open a window to show graphical results.

If you have ever opened the Windows Command Prompt or macOS Terminal, you have seen a CLI. If you have already taken The Carpentries’ courses on the UNIX Shell or Version Control, you have used the CLI on your local machine extensively. The only leap to be made here is to open a CLI on a remote machine, while taking some precautions so that other folks on the network can’t see (or change) the commands you’re running or the results the remote machine sends back. We will use the Secure SHell protocol (or SSH) to open an encrypted network connection between two machines, allowing you to send & receive text and data without having to worry about prying eyes.

SSH clients are usually command-line tools, where you provide the remote

machine address as the only required argument. If your username on the remote

system differs from what you use locally, you must provide that as well. If

your SSH client has a graphical front-end, such as PuTTY or MobaXterm, you will

set these arguments before clicking “connect.” From the terminal, you’ll write

something like ssh userName@hostname, where the argument is just like an

email address: the “@” symbol is used to separate the personal ID from the

address of the remote machine.

When logging in to a laptop, tablet, or other personal device, a username, password, or pattern are normally required to prevent unauthorized access. In these situations, the likelihood of somebody else intercepting your password is low, since logging your keystrokes requires a malicious exploit or physical access. For systems like Baskerville running an SSH server, anybody on the network can log in, or try to. Since usernames are often public or easy to guess, your password is often the weakest link in the security chain. Many clusters therefore forbid password-based login, requiring instead that you generate and configure a public-private key pair with a much stronger password. Even if your cluster does not require it, the next section will guide you through the use of SSH keys and an SSH agent to both strengthen your security and make it more convenient to log in to remote systems.

Better Security With SSH Keys

The Lesson Setup provides instructions for installing a shell application with SSH. If you have not done so already, please open that shell application with a Unix-like command line interface to your system.

SSH keys are an alternative method for authentication to obtain access to remote computing systems. They can also be used for authentication when transferring files or for accessing remote version control systems (such as GitHub). In this section you will create a pair of SSH keys:

- a private key which you keep on your own computer, and

- a public key which can be placed on any remote system you will access.

Private keys are your secure digital passport

A private key that is visible to anyone but you should be considered compromised, and must be destroyed. This includes having improper permissions on the directory it (or a copy) is stored in, traversing any network that is not secure (encrypted), attachment on unencrypted email, and even displaying the key on your terminal window.

Protect this key as if it unlocks your front door. In many ways, it does.

Regardless of the software or operating system you use, please choose a strong password or passphrase to act as another layer of protection for your private SSH key.

Considerations for SSH Key Passwords

When prompted, enter a strong password that you will remember. There are two common approaches to this:

- Create a memorable passphrase with some punctuation and number-for-letter substitutions, 32 characters or longer. Street addresses work well; just be careful of social engineering or public records attacks.

- Use a password manager and its built-in password generator with all character classes, 25 characters or longer. KeePass and BitWarden are two good options.

- Nothing is less secure than a private key with no password. If you skipped password entry by accident, go back and generate a new key pair with a strong password.

SSH Keys on Linux, Mac, MobaXterm, and Windows Subsystem for Linux

Once you have opened a terminal, check for existing SSH keys and filenames since existing SSH keys are overwritten.

[user@laptop ~]$ ls ~/.ssh/

If ~/.ssh/id_ed25519 already exists, you will need to specify

a different name for the new key-pair.

Generate a new public-private key pair using the following command, which will

produce a stronger key than the ssh-keygen default by invoking these flags:

-a(default is 16): number of rounds of passphrase derivation; increase to slow down brute force attacks.-t(default is rsa): specify the “type” or cryptographic algorithm.ed25519specifies EdDSA with a 256-bit key; it is faster than RSA with a comparable strength.-f(default is /home/user/.ssh/id_algorithm): filename to store your private key. The public key filename will be identical, with a.pubextension added.

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh-keygen -a 100 -f ~/.ssh/id_ed25519 -t ed25519

When prompted, enter a strong password with the above considerations in mind. Note that the terminal will not appear to change while you type the password: this is deliberate, for your security. You will be prompted to type it again, so don’t worry too much about typos.

Take a look in ~/.ssh (use ls ~/.ssh). You should see two new files:

- your private key (

~/.ssh/id_ed25519): do not share with anyone! - the shareable public key (

~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub): if a system administrator asks for a key, this is the one to send. It is also safe to upload to websites such as GitHub: it is meant to be seen.

Use RSA for Older Systems

If key generation failed because ed25519 is not available, try using the older (but still strong and trustworthy) RSA cryptosystem. Again, first check for an existing key:

[user@laptop ~]$ ls ~/.ssh/If

~/.ssh/id_rsaalready exists, you will need to specify choose a different name for the new key-pair. Generate it as above, with the following extra flags:

-bsets the number of bits in the key. The default is 2048. EdDSA uses a fixed key length, so this flag would have no effect.-o(no default): use the OpenSSH key format, rather than PEM.[user@laptop ~]$ ssh-keygen -a 100 -b 4096 -f ~/.ssh/id_rsa -o -t rsaWhen prompted, enter a strong password with the above considerations in mind.

Take a look in

~/.ssh(usels ~/.ssh). You should see two new files:

- your private key (

~/.ssh/id_rsa): do not share with anyone!- the shareable public key (

~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub): if a system administrator asks for a key, this is the one to send. It is also safe to upload to websites such as GitHub: it is meant to be seen.

SSH Keys on PuTTY

If you are using PuTTY on Windows, download and use puttygen to generate the

key pair. See the PuTTY documentation for details.

- Select

EdDSAas the key type. - Select

255as the key size or strength. - Click on the “Generate” button.

- You do not need to enter a comment.

- When prompted, enter a strong password with the above considerations in mind.

- Save the keys in a folder no other users of the system can read.

Take a look in the folder you specified. You should see two new files:

- your private key (

id_ed25519): do not share with anyone! - the shareable public key (

id_ed25519.pub): if a system administrator asks for a key, this is the one to send. It is also safe to upload to websites such as GitHub: it is meant to be seen.

SSH Agent for Easier Key Handling

An SSH key is only as strong as the password used to unlock it, but on the other hand, typing out a complex password every time you connect to a machine is tedious and gets old very fast. This is where the SSH Agent comes in.

Using an SSH Agent, you can type your password for the private key once, then have the Agent remember it for some number of hours or until you log off. Unless some nefarious actor has physical access to your machine, this keeps the password safe, and removes the tedium of entering the password multiple times.

Just remember your password, because once it expires in the Agent, you have to type it in again.

SSH Agents on Linux, macOS, and Windows

Open your terminal application and check if an agent is running:

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh-add -l

-

If you get an error like this one,

Error connecting to agent: No such file or directory… then you need to launch the agent as follows:

[user@laptop ~]$ eval $(ssh-agent)What’s in a

$(...)?The syntax of this SSH Agent command is unusual, based on what we’ve seen in the UNIX Shell lesson. This is because the

ssh-agentcommand creates opens a connection that only you have access to, and prints a series of shell commands that can be used to reach it – but does not execute them![user@laptop ~]$ ssh-agentSSH_AUTH_SOCK=/tmp/ssh-Zvvga2Y8kQZN/agent.131521; export SSH_AUTH_SOCK; SSH_AGENT_PID=131522; export SSH_AGENT_PID; echo Agent pid 131522;The

evalcommand interprets this text output as commands and allows you to access the SSH Agent connection you just created.You could run each line of the

ssh-agentoutput yourself, and achieve the same result. Usingevaljust makes this easier. -

Otherwise, your agent is already running: don’t mess with it.

Add your key to the agent, with session expiration after 8 hours:

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh-add -t 8h ~/.ssh/id_ed25519

Enter passphrase for .ssh/id_ed25519:

Identity added: .ssh/id_ed25519

Lifetime set to 86400 seconds

For the duration (8 hours), whenever you use that key, the SSH Agent will provide the key on your behalf without you having to type a single keystroke.

SSH Agent on PuTTY

If you are using PuTTY on Windows, download and use pageant as the SSH agent.

See the PuTTY documentation.

Transfer Your Public Key

Baskerville

For Baskerville, please paste your public SSH key into Baskerville Admin under the

'Configure account / reset password'link and disregard the secure copy tool below.

Use the secure copy tool to send your public key to the cluster.

[user@laptop ~]$ scp ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:~/

Log In to the Cluster

Go ahead and open your terminal or graphical SSH client, then log in to the

cluster. Replace yourUsername with your username or the one

supplied by the instructors.

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk

You may be asked for your password, and/or a One Time Passcode for Multi Factor Authentication. Watch out: the characters you type after

the password prompt are not displayed on the screen. Normal output will resume

once you press Enter.

You may have noticed that the prompt changed when you logged into the remote

system using the terminal (if you logged in using PuTTY this will not apply

because it does not offer a local terminal). This change is important because

it can help you distinguish on which system the commands you type will be run

when you pass them into the terminal. This change is also a small complication

that we will need to navigate throughout the workshop. Exactly what is displayed

as the prompt (which conventionally ends in $) in the terminal when it is

connected to the local system and the remote system will typically be different

for every user. We still need to indicate which system we are entering commands

on though so we will adopt the following convention:

[user@laptop ~]$when the command is to be entered on a terminal connected to your local computer[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$when the command is to be entered on a terminal connected to the remote system$when it really doesn’t matter which system the terminal is connected to.

Looking Around Your Remote Home

Very often, many users are tempted to think of a high-performance computing

installation as one giant, magical machine. Sometimes, people will assume that

the computer they’ve logged onto is the entire computing cluster. So what’s

really happening? What computer have we logged on to? The name of the current

computer we are logged onto can be checked with the hostname command. (You

may also notice that the current hostname is also part of our prompt!)

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ hostname

bask-pg0310u18a.cluster.baskerville.ac.uk

So, we’re definitely on the remote machine. Next, let’s find out where we are

by running pwd to print the working directory.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ pwd

/bask/homes/y/yourUsername

Great, we know where we are! Let’s see what’s in our current directory:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ ls

id_ed25519.pub

The system administrators may have configured your home directory with some helpful files, folders, and links (shortcuts) to space reserved for you on other filesystems. If they did not, your home directory may appear empty. To double-check, include hidden files in your directory listing:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ ls -a

. .bashrc id_ed25519.pub

.. .ssh

In the first column, . is a reference to the current directory and .. a

reference to its parent (/bask/homes/y). You may or may not see

the other files, or files like them: .bashrc is a shell configuration file,

which you can edit with your preferences; and .ssh is a directory storing SSH

keys and a record of authorized connections.

Install Your SSH Key

There May Be a Better Way

Policies and practices for handling SSH keys vary between HPC clusters: follow any guidance provided by the cluster administrators or documentation. In particular, if there is an online portal for managing SSH keys, use that instead of the directions outlined here. For Baskerville, please paste your public SSH key into Baskerville Admin under the

'Configure account / reset password'link, and disregard the rest of this section.

If you transferred your SSH public key with scp, you should see

id_ed25519.pub in your home directory. To “install” this key, it must be

listed in a file named authorized_keys under the .ssh folder.

If the .ssh folder was not listed above, then it does not yet

exist: create it.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ mkdir ~/.ssh

Now, use cat to print your public key, but redirect the output, appending it

to the authorized_keys file:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ cat ~/id_ed25519.pub >> ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

That’s all! Disconnect, then try to log back into the remote: if your key and agent have been configured correctly, you should not be prompted for the password for your SSH key.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ logout

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk

Key Points

An HPC system is a set of networked machines.

HPC systems typically provide login nodes and a set of worker nodes.

The resources found on independent (worker) nodes can vary in volume and type (amount of RAM, processor architecture, availability of network mounted filesystems, etc.).

Files saved on one node are available on all nodes.

Exploring Remote Resources

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How does my local computer compare to the remote systems?

How does the login node compare to the compute nodes?

Are all compute nodes alike?

Objectives

Survey system resources using

nproc,free, and the queuing systemCompare & contrast resources on the local machine, login node, and worker nodes

Learn about the various filesystems on the cluster using

dfFind out

whoelse is logged inAssess the number of idle and occupied nodes

Look Around the Remote System

If you have not already connected to Baskerville, please do so now:

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk

Take a look at your home directory on the remote system:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ ls

What’s different between your machine and the remote?

Open a second terminal window on your local computer and run the

lscommand (without logging in to Baskerville). What differences do you see?Solution

You would likely see something more like this:

[user@laptop ~]$ lsApplications Documents Library Music Public Desktop Downloads Movies PicturesThe remote computer’s home directory shares almost nothing in common with the local computer: they are completely separate systems!

Most high-performance computing systems run the Linux operating system, which

is built around the UNIX Filesystem Hierarchy Standard. Instead of

having a separate root for each hard drive or storage medium, all files and

devices are anchored to the “root” directory, which is /:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ ls /

bin etc lib64 proc sbin sys var

boot bask mnt root scratch tmp working

dev lib opt run srv usr

The /bask/homes/y directory is the one where

we generally want to keep all of our files (Note: on Baskerville, the last letter of the directory corresponds to the first letter of your username). Other folders on a UNIX OS contain

system files and change as you install new software or upgrade your OS.

Using HPC filesystems

On HPC systems, you have a number of places where you can store your files. These differ in both the amount of space allocated and whether or not they are backed up.

- Home – often a network filesystem, data stored here is available throughout the HPC system, and often backed up periodically. Files stored here are typically slower to access, the data is actually stored on another computer and is being transmitted and made available over the network!

- Scratch – typically faster than the networked Home directory, but not usually backed up, and should not be used for long term storage.

- Work – sometimes provided as an alternative to Scratch space, Work is a fast file system accessed over the network. Typically, this will have higher performance than your home directory, but lower performance than Scratch; it may not be backed up. It differs from Scratch space in that files in a work file system are not automatically deleted for you: you must manage the space yourself.

Nodes

Individual computers that compose a cluster are typically called nodes (although you will also hear people call them servers, computers and machines). On a cluster, there are different types of nodes for different types of tasks. The node where you are right now is called the login node, head node, landing pad, or submit node. A login node serves as an access point to the cluster.

As a gateway, the login node should not be used for time-consuming or resource-intensive tasks. You should be alert to this, and check with your site’s operators or documentation for details of what is and isn’t allowed. It is well suited for uploading and downloading files, setting up software, and running tests. Generally speaking, in these lessons, we will avoid running jobs on the login node.

Who else is logged in to the login node?

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ who

This may show only your user ID, but there are likely several other people (including fellow learners) connected right now.

Dedicated Transfer Nodes

If you want to transfer larger amounts of data to or from the cluster, some systems offer dedicated nodes for data transfers only. The motivation for this lies in the fact that larger data transfers should not obstruct operation of the login node for anybody else. Check with your cluster’s documentation or its support team if such a transfer node is available. As a rule of thumb, consider all transfers of a volume larger than 500 MB to 1 GB as large. But these numbers change, e.g., depending on the network connection of yourself and of your cluster or other factors.

The real work on a cluster gets done by the compute (or worker) nodes. compute nodes come in many shapes and sizes, but generally are dedicated to long or hard tasks that require a lot of computational resources.

All interaction with the compute nodes is handled by a specialized piece of software called a scheduler (the scheduler used in this lesson is called Slurm). We’ll learn more about how to use the scheduler to submit jobs next, but for now, it can also tell us more information about the compute nodes.

For example, we can view all of the compute nodes by running the command

sinfo (Note: command not available on Baskerville).

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sinfo

PARTITION AVAIL TIMELIMIT NODES STATE NODELIST

normal* up 7-00:00:00 1 down* c5-12

normal* up 7-00:00:00 87 mix c1-[7,13-15,19,22-24,28,31,33,3.......

normal* up 7-00:00:00 110 alloc c1-[1-6,8-9,11-12,16-18,20-21,........

normal* up 7-00:00:00 1 idle c1-10

bigmem up 14-00:00:0 1 drain c6-3

bigmem up 14-00:00:0 10 mix c3-[29-31,53,56],c6-[1,4-7]

bigmem up 14-00:00:0 1 alloc c6-2

bigmem up 14-00:00:0 24 idle c3-[32-52,54-55],c6-8

accel up 14-00:00:0 3 mix c7-[1-2,8]

accel up 14-00:00:0 5 alloc c7-[3-7]

optimist up infinite 1 down* c5-12

optimist up infinite 1 drain c6-3

optimist up infinite 100 mix c1-[7,13-15,19,22-24,28,31,33,35,37...

optimist up infinite 116 alloc c1-[1-6,8-9,11-12,16-18,20-21,25-27...

optimist up infinite 25 idle c1-10,c3-[32-52,54-55],c6-8

A lot of the nodes are busy running work for other users: we are not alone here!

There are also specialized machines used for managing disk storage, user authentication, and other infrastructure-related tasks. Although we do not typically logon to or interact with these machines directly, they enable a number of key features like ensuring our user account and files are available throughout the HPC system.

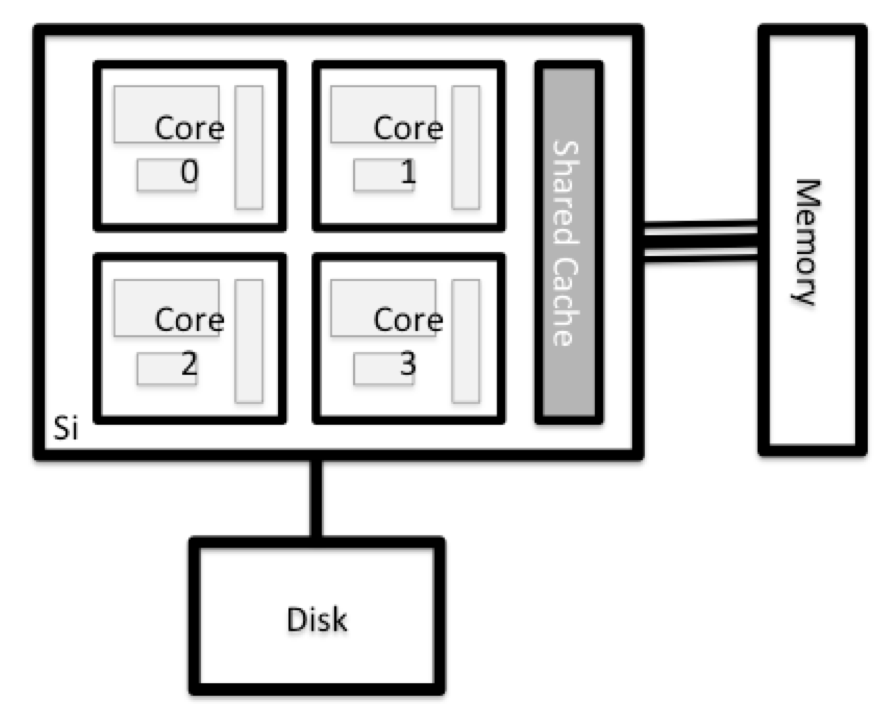

What’s in a Node?

All of the nodes in an HPC system have the same components as your own laptop or desktop: CPUs (sometimes also called processors or cores), memory (or RAM), and disk space. CPUs are a computer’s tool for actually running programs and calculations. Information about a current task is stored in the computer’s memory. Disk refers to all storage that can be accessed like a file system. This is generally storage that can hold data permanently, i.e. data is still there even if the computer has been restarted. While this storage can be local (a hard drive installed inside of it), it is more common for nodes to connect to a shared, remote fileserver or cluster of servers.

Explore Your Computer

Try to find out the number of CPUs and amount of memory available on your personal computer.

Note that, if you’re logged in to the remote computer cluster, you need to log out first. To do so, type

Ctrl+dorexit:[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ exit [user@laptop ~]$Solution

There are several ways to do this. Most operating systems have a graphical system monitor, like the Windows Task Manager. More detailed information can be found on the command line:

- Run system utilities

[user@laptop ~]$ nproc --all [user@laptop ~]$ free -m- Read from

/proc[user@laptop ~]$ cat /proc/cpuinfo [user@laptop ~]$ cat /proc/meminfo- Run system monitor

[user@laptop ~]$ htop

Explore the Login Node

Now compare the resources of your computer with those of the login node.

Solution

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk [yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ nproc --all [yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ free -mYou can get more information about the processors using

lscpu, and a lot of detail about the memory by reading the file/proc/meminfo:[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ less /proc/meminfoYou can also explore the available filesystems using

dfto show disk free space. The-hflag renders the sizes in a human-friendly format, i.e., GB instead of B. The type flag-Tshows what kind of filesystem each resource is.[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ df -ThDifferent results from

df

- The local filesystems (ext, tmp, xfs, zfs) will depend on whether you’re on the same login node (or compute node, later on).

- Networked filesystems (beegfs, cifs, gpfs, nfs, pvfs) will be similar – but may include yourUsername, depending on how it is mounted.

Shared Filesystems

This is an important point to remember: files saved on one node (computer) are often available everywhere on the cluster!

Explore a Worker Node

Finally, let’s look at the resources available on the worker nodes where your jobs will actually run. Try running this command to see the name, CPUs and memory available on the worker nodes (the instructors will give you the ID of the compute node to use):

sinfo --node c3-12 -o "%n %c %m"

Compare Your Computer, the Login Node and the Compute Node

Compare your laptop’s number of processors and memory with the numbers you see on the cluster login node and compute node. What implications do you think the differences might have on running your research work on the different systems and nodes?

Solution

Compute nodes are usually built with processors that have higher core-counts than the login node or personal computers in order to support highly parallel tasks. Compute nodes usually also have substantially more memory (RAM) installed than a personal computer. More cores tends to help jobs that depend on some work that is easy to perform in parallel, and more, faster memory is key for large or complex numerical tasks.

Differences Between Nodes

Many HPC clusters have a variety of nodes optimized for particular workloads. Some nodes may have larger amount of memory, or specialized resources such as Graphics Processing Units (GPUs or “video cards”).

With all of this in mind, we will now cover how to talk to the cluster’s scheduler, and use it to start running our scripts and programs!

Key Points

An HPC system is a set of networked machines.

HPC systems typically provide login nodes and a set of compute nodes.

The resources found on independent (worker) nodes can vary in volume and type (amount of RAM, processor architecture, availability of network mounted filesystems, etc.).

Files saved on shared storage are available on all nodes.

The login node is a shared machine: be considerate of other users.

Scheduler Fundamentals

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

What is a scheduler and why does a cluster need one?

How do I launch a program to run on a compute node in the cluster?

How do I capture the output of a program that is run on a node in the cluster?

Objectives

Submit a simple script to the cluster.

Monitor the execution of jobs using command line tools.

Inspect the output and error files of your jobs.

Find the right place to put large datasets on the cluster.

Job Scheduler

An HPC system might have thousands of nodes and thousands of users. How do we decide who gets what and when? How do we ensure that a task is run with the resources it needs? This job is handled by a special piece of software called the scheduler. On an HPC system, the scheduler manages which jobs run where and when.

The following illustration compares these tasks of a job scheduler to a waiter in a restaurant. If you can relate to an instance where you had to wait for a while in a queue to get in to a popular restaurant, then you may now understand why sometimes your job do not start instantly as in your laptop.

The scheduler used in this lesson is Slurm. Although Slurm is not used everywhere, running jobs is quite similar regardless of what software is being used. The exact syntax might change, but the concepts remain the same.

Running a Batch Job

The most basic use of the scheduler is to run a command non-interactively. Any command (or series of commands) that you want to run on the cluster is called a job, and the process of using a scheduler to run the job is called batch job submission.

In this case, the job we want to run is a shell script – essentially a text file containing a list of UNIX commands to be executed in a sequential manner. Our shell script will have three parts:

- On the very first line, add

#!/bin/bash. The#!(pronounced “hash-bang” or “shebang”) tells the computer what program is meant to process the contents of this file. In this case, we are telling it that the commands that follow are written for the command-line shell (what we’ve been doing everything in so far). - Anywhere below the first line, we’ll add an

echocommand with a friendly greeting. When run, the shell script will print whatever comes afterechoin the terminal.echo -nwill print everything that follows, without ending the line by printing the new-line character.

- On the last line, we’ll invoke the

hostnamecommand, which will print the name of the machine the script is run on.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ nano example-job.sh

#!/bin/bash

echo -n "This script is running on "

hostname

Creating Our Test Job

Run the script. Does it execute on the cluster or just our login node?

Solution

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ bash example-job.shThis script is running on bask-pg0310u18a.cluster.baskerville.ac.uk

This script ran on the login node, but we want to take advantage of

the compute nodes: we need the scheduler to queue up example-job.sh

to run on a compute node.

To submit this task to the scheduler, we use the

sbatch command.

This creates a job which will run the script when dispatched to

a compute node which the queuing system has identified as being

available to perform the work.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sbatch --qos=<input_qos> example-job.sh

Submitted batch job 137860

And that’s all we need to do to submit a job. Our work is done – now the

scheduler takes over and tries to run the job for us. While the job is waiting

to run, it goes into a list of jobs called the queue. To check on our job’s

status, we check the queue using the command

squeue -u yourUsername.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ squeue -u yourUsername

JOBID PARTITION NAME USER ST TIME NODES NODELIST(REASON)

137860 normal example- usernm R 0:02 1 c5-59

Where’s the Output?

On the login node, this script printed output to the terminal – but now, when

squeueshows the job has finished, nothing was printed to the terminal.Cluster job output is typically redirected to a file in the directory you launched it from. Use

lsto find andcatto read the file.

Customising a Job

The job we just ran used all of the scheduler’s default options. In a real-world scenario, that’s probably not what we want. The default options represent a reasonable minimum. Chances are, we will need more cores, more memory, more time, among other special considerations. To get access to these resources we must customize our job script.

Comments in UNIX shell scripts (denoted by #) are typically ignored, but

there are exceptions. For instance the special #! comment at the beginning of

scripts specifies what program should be used to run it (you’ll typically see

#!/usr/bin/env bash). Schedulers like Slurm also

have a special comment used to denote special scheduler-specific options.

Though these comments differ from scheduler to scheduler,

Slurm’s special comment is #SBATCH. Anything

following the #SBATCH comment is interpreted as an

instruction to the scheduler.

Let’s illustrate this by example. By default, a job’s name is the name of the

script, but the -J option can be used to change the

name of a job. Add an option to the script:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ cat example-job.sh

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH -J hello-world

echo -n "This script is running on "

hostname

Submit the job and monitor its status:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sbatch --qos=<input_qos> example-job.sh

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ squeue -u yourUsername

JOBID ACCOUNT NAME ST REASON START_TIME TIME TIME_LEFT NODES CPUS

38191 yourAccount hello-wo PD Priority N/A 0:00 1:00:00 1 1

Fantastic, we’ve successfully changed the name of our job!

Resource Requests

What about more important changes, such as the number of cores and memory for our jobs? One thing that is absolutely critical when working on an HPC system is specifying the resources required to run a job. This allows the scheduler to find the right time and place to schedule our job. If you do not specify requirements (such as the amount of time you need), you will likely be stuck with your site’s default resources, which is probably not what you want.

The following are several key resource requests:

-

--ntasks=<ntasks>or-n <ntasks>: How many CPU cores does your job need, in total? -

--time <days-hours:minutes:seconds>or-t <days-hours:minutes:seconds>: How much real-world time (walltime) will your job take to run? The<days>part can be omitted. -

--mem=<megabytes>: How much memory on a node does your job need in megabytes? You can also specify gigabytes using by adding a little “g” afterwards (example:--mem=5g) -

--nodes=<nnodes>or-N <nnodes>: How many separate machines does your job need to run on? Note that if you setntasksto a number greater than what one machine can offer, Slurm will set this value automatically.

Note that just requesting these resources does not make your job run faster, nor does it necessarily mean that you will consume all of these resources. It only means that these are made available to you. Your job may end up using less memory, or less time, or fewer nodes than you have requested, and it will still run.

It’s best if your requests accurately reflect your job’s requirements. We’ll talk more about how to make sure that you’re using resources effectively in a later episode of this lesson.

Submitting Resource Requests

Modify our

hostnamescript so that it runs for a minute, then submit a job for it on the cluster.Solution

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ cat example-job.sh#!/bin/bash #SBATCH -t 00:01 # timeout in HH:MM echo -n "This script is running on " sleep 20 # time in seconds hostname[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sbatch --qos=<input_qos> example-job.shWhy are the Slurm runtime and

sleeptime not identical?

Resource requests are typically binding. If you exceed them, your job will be killed. Let’s use wall time as an example. We will request 1 minute of wall time, and attempt to run a job for two minutes.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ cat example-job.sh

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH -J long_job

#SBATCH -t 00:01 # timeout in HH:MM

echo "This script is running on ... "

sleep 240 # time in seconds

hostname

Submit the job and wait for it to finish. Once it is has finished, check the log file.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sbatch --qos=<input_qos> example-job.sh

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ squeue -u yourUsername

cat slurm-38193.out

This job is running on: c1-14

slurmstepd: error: *** JOB 38193 ON gra533 CANCELLED AT 2017-07-02T16:35:48

DUE TO TIME LIMIT ***

Our job was killed for exceeding the amount of resources it requested. Although this appears harsh, this is actually a feature. Strict adherence to resource requests allows the scheduler to find the best possible place for your jobs. Even more importantly, it ensures that another user cannot use more resources than they’ve been given. If another user messes up and accidentally attempts to use all of the cores or memory on a node, Slurm will either restrain their job to the requested resources or kill the job outright. Other jobs on the node will be unaffected. This means that one user cannot mess up the experience of others, the only jobs affected by a mistake in scheduling will be their own.

Cancelling a Job

Sometimes we’ll make a mistake and need to cancel a job. This can be done with

the scancel command. Let’s submit a job and then cancel it using

its job number (remember to change the walltime so that it runs long enough for

you to cancel it before it is killed!).

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sbatch --qos=<input_qos> example-job.sh

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ squeue -u yourUsername

Submitted batch job 38759

JOBID ACCOUNT NAME ST REASON TIME TIME_LEFT NODES CPUS

38759 yourAccount example-job.sh PD Priority 0:00 1:00 1 1

Now cancel the job with its job number (printed in your terminal). A clean return of your command prompt indicates that the request to cancel the job was successful.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ scancel 38759

# It might take a minute for the job to disappear from the queue...

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ squeue -u yourUsername

JOBID USER ACCOUNT NAME ST REASON START_TIME TIME TIME_LEFT NODES CPUS

Cancelling multiple jobs

We can also cancel all of our jobs at once using the

-uoption. This will delete all jobs for a specific user (in this case us). Note that you can only delete your own jobs.Try submitting multiple jobs and then cancelling them all with

scancel -u yourUsername.

Other Types of Jobs

Up to this point, we’ve focused on running jobs in batch mode. Slurm also provides the ability to start an interactive session.

There are very frequently tasks that need to be done interactively. Creating an

entire job script might be overkill, but the amount of resources required is

too much for a login node to handle. A good example of this might be building a

genome index for alignment with a tool like HISAT2. Fortunately, we

can run these types of tasks as a one-off with srun.

srun runs a single command on the cluster and then exits. Let’s demonstrate

this by running the hostname command with srun. (We can cancel an srun

job with Ctrl-c.)

srun hostname

gra752

srun accepts all of the same options as sbatch. However, instead of

specifying these in a script, these options are specified on the command-line

when starting a job. To submit a job that uses 2 CPUs for instance, we could

use the following command:

srun -n 2 echo "This job will use 2 CPUs."

This job will use 2 CPUs.

This job will use 2 CPUs.

Typically, the resulting shell environment will be the same as that for

sbatch.

Interactive jobs

Sometimes, you will need a lot of resource for interactive use. Perhaps it’s

our first time running an analysis or we are attempting to debug something that

went wrong with a previous job. Fortunately, Slurm makes it easy to start an

interactive job with srun:

srun --pty bash

You should be presented with a bash prompt. Note that the prompt will likely

change to reflect your new location, in this case the compute node we are

logged on. You can also verify this with hostname.

Creating remote graphics

To see graphical output inside your jobs, you need to use X11 forwarding. To connect with this feature enabled, use the

-Yoption when you login withsshwith the commandssh -Y username@host.To demonstrate what happens when you create a graphics window on the remote node, use the

xeyescommand. A relatively adorable pair of eyes should pop up (pressCtrl-cto stop). If you are using a Mac, you must have installed XQuartz (and restarted your computer) for this to work.If your cluster has the slurm-spank-x11 plugin installed, you can ensure X11 forwarding within interactive jobs by using the

--x11option forsrunwith the commandsrun --x11 --pty bash.

When you are done with the interactive job, type exit to quit your session.

Key Points

The scheduler handles how compute resources are shared between users.

A job is just a shell script.

Request slightly more resources than you will need.

Accessing software via Modules

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How do we load and unload software packages?

Objectives

Load and use a software package.

Explain how the shell environment changes when the module mechanism loads or unloads packages.

On a high-performance computing system, it is seldom the case that the software we want to use is available when we log in. It is installed, but we will need to “load” it before it can run.

Before we start using individual software packages, however, we should understand the reasoning behind this approach. The three biggest factors are:

- software incompatibilities

- versioning

- dependencies

Software incompatibility is a major headache for programmers. Sometimes the

presence (or absence) of a software package will break others that depend on

it. Two of the most famous examples are Python 2 and 3 and C compiler versions.

Python 3 famously provides a python command that conflicts with that provided

by Python 2. Software compiled against a newer version of the C libraries and

then used when they are not present will result in a nasty 'GLIBCXX_3.4.20'

not found error, for instance.

Software versioning is another common issue. A team might depend on a certain package version for their research project - if the software version was to change (for instance, if a package was updated), it might affect their results. Having access to multiple software versions allow a set of researchers to prevent software versioning issues from affecting their results.

Dependencies are where a particular software package (or even a particular version) depends on having access to another software package (or even a particular version of another software package). For example, the VASP materials science software may depend on having a particular version of the FFTW (Fastest Fourier Transform in the West) software library available for it to work.

Environment Modules

Environment modules are the solution to these problems. A module is a self-contained description of a software package – it contains the settings required to run a software package and, usually, encodes required dependencies on other software packages.

There are a number of different environment module implementations commonly

used on HPC systems: the two most common are TCL modules and Lmod. Both of

these use similar syntax and the concepts are the same so learning to use one

will allow you to use whichever is installed on the system you are using. In

both implementations the module command is used to interact with environment

modules. An additional subcommand is usually added to the command to specify

what you want to do. For a list of subcommands you can use module -h or

module help. As for all commands, you can access the full help on the man

pages with man module.

On login you may start out with a default set of modules loaded or you may start out with an empty environment; this depends on the setup of the system you are using.

Listing Available Modules

To see available software modules, use module avail:

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ module avail

---------------------- /cluster/modulefiles/all -------------------------

4ti2/1.6.9-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1 gmsh/4.5.6-foss-2019b-Python-3.7.4

ABySS/2.0.2-gompi-2019a gnuplot/5.2.6-GCCcore-8.2.0

AdapterRemoval/2.3.1-foss-2018b gnuplot/5.2.8-GCCcore-8.3.0

AdapterRemoval/2.3.1-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1 Go/1.13.1

ADF/2019.103+StaticMKL gompi/2018b

AdmixTools/5.1-GCC-7.3.0-2.30 gompi/2019a

ADMIXTURE/1.3.0 gompi/2019b

[removed most of the output here for clarity]

----------------------- /cluster/modulefiles/external ---------------------

appusage/1.0 hpcx/2.4 hpcx/2.5 hpcx/2.6

Where:

S: Module is Sticky, requires --force to unload or purge

L: Module is loaded

Aliases: Aliases exist: foo/1.2.3 (1.2) means that "module load foo/1.2"

will load foo/1.2.3

Use "module spider" to find all possible modules.

Use "module keyword key1 key2 ..." to search for all possible modules matching

any of the "keys".

Listing Currently Loaded Modules

You can use the module list command to see which modules you currently have

loaded in your environment. If you have no modules loaded, you will see a

message telling you so

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ module list

No Modulefiles Currently Loaded.

Loading and Unloading Software

To load a software module, use module load. In this example we will use

Python 3.

Initially, Python 3 is not loaded. We can test this by using the which

command. which looks for programs the same way that Bash does, so we can use

it to tell us where a particular piece of software is stored.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ which python3

/usr/bin/which:no python3 in

(/opt/software/slurm/16.05.9/bin:

/cvmfs/soft.computecanada.ca/easybuild/software/2017/Core/imkl/11.3.4.258/bin:

/opt/software/bin:/opt/puppetlabs/puppet/bin:/opt/software/slurm/current/bin:

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/usr/local/sbin:

/usr/sbin:/home/yourUsername/.local/bin:/home/yourUsername/bin)

We can load the python3 command with module load:

module load Python/3.7.2-GCCcore-8.2.0

which python3

/cluster/software/Python/3.7.2-GCCcore-8.2.0/bin/python

So, what just happened?

To understand the output, first we need to understand the nature of the $PATH

environment variable. $PATH is a special environment variable that controls

where a UNIX system looks for software. Specifically $PATH is a list of

directories (separated by :) that the OS searches through for a command

before giving up and telling us it can’t find it. As with all environment

variables we can print it out using echo.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ echo $PATH

/cluster/software/Python/3.8.2-GCCcore-9.3.0/bin:

/cluster/software/XZ/5.2.5-GCCcore-9.3.0/bin:

/cluster/software/bzip2/1.0.8-GCCcore-9.3.0/bin:

/cluster/software/binutils/2.34-GCCcore-9.3.0/bin:

/cluster/software/GCCcore/9.3.0/bin:/node/bin:/usr/local/bin:

/usr/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/sbin:/cluster/bin:

/cluster/home/sabryr/.local/bin:/cluster/home/sabryr/bin

You’ll notice a similarity to the output of the which command. In this case,

there’s only one difference: the different directory at the beginning. When we

ran the module load command, it added a directory to the beginning of our

$PATH. Let’s examine what’s there:

ls /cluster/software/Python/3.8.2-GCCcore-9.3.0/bin

2to3 idle3.7 pytest rst2odt.py

2to3-3.7 isympy python rst2pseudoxml.py

chardetect netaddr python3 rst2s5.py

cygdb nosetests python3.7 rst2xetex.py

cython nosetests-3.7 python3.7-config rst2xml.py

cythonize pasteurize python3.7m rstpep2html.py

dijitso pbr python3.7m-config runxlrd.py

easy_install pip python3-config sphinx-apidoc

easy_install-3.7 pip3 pyvenv sphinx-autogen

f2py pip3.7 pyvenv-3.7 sphinx-build

f2py3 pybabel rst2html4.py sphinx-quickstart

f2py3.7 __pycache__ rst2html5.py tabulate

ffc pydoc3 rst2html.py virtualenv

ffc-3 pydoc3.7 rst2latex.py wheel

futurize pygmentize rst2man.py

idle3 py.test rst2odt_prepstyles.py

Taking this to its conclusion, module load will add software to your $PATH.

It “loads” software. A special note on this - depending on which version of the

module program that is installed at your site, module load will also load

required software dependencies.

To demonstrate, let’s use module list. module list shows all loaded

software modules.

module list

Currently Loaded Modules:

1) StdEnv (S) 6) libreadline/8.0-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

2) GCCcore/8.2.0 7) XZ/5.2.4-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

3) bzip2/1.0.6-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 8) GMP/6.1.2-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

4) zlib/1.2.11-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 9) libffi/3.2.1-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

5) ncurses/6.1-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 10) Python/3.7.2-GCCcore-8.2.0

Where:

S: Module is Sticky, requires --force to unload or purge

H: Hidden Module

module load Beast/2.5.2-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1

module list

Currently Loaded Modules:

1) StdEnv (S) 9) libffi/3.2.1-GCCcore-8.2.0

2) GCCcore/8.2.0 10) Python/3.7.2-GCCcore-8.2.0

3) bzip2/1.0.6-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 11) binutils/2.31.1-GCCcore-8.2.0

4) zlib/1.2.11-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 12) GCC/8.2.0-2.31.1

5) ncurses/6.1-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 13) Java/11.0.2

6) libreadline/8.0-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 14) beagle-lib/3.1.2-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1

7) XZ/5.2.4-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 15) Beast/2.5.2-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1

8) GMP/6.1.2-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

Where:

S: Module is Sticky, requires --force to unload or purge

H: Hidden Module

So in this case, loading the beast module (a bioinformatics software

package), also loaded Java/11.0.2 and beagle-lib/3.1.2-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1 as

well. Let’s try unloading the beast package.

module unload Beast/2.5.2-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1

module list

Currently Loaded Modules:

1) StdEnv (S) 8) GMP/6.1.2-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

2) GCCcore/8.2.0 9) libffi/3.2.1-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

3) bzip2/1.0.6-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 10) Python/3.7.2-GCCcore-8.2.0

4) zlib/1.2.11-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 11) binutils/2.31.1-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H)

5) ncurses/6.1-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 12) GCC/8.2.0-2.31.1

6) libreadline/8.0-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 13) Java/11.0.2

7) XZ/5.2.4-GCCcore-8.2.0 (H) 14) beagle-lib/3.1.2-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1

Where:

S: Module is Sticky, requires --force to unload or purge

H: Hidden Module

So using module unload “un-loads” a module along with its dependencies. If we

wanted to unload everything at once, we could run module purge (unloads

everything).

module purge

The following modules were not unloaded:

(Use "module --force purge" to unload all):

1) StdEnv

Note that module purge is informative. It lets us know that all but a default

set of packages have been unloaded (and how to actually unload these if we

truly so desired).

Note that this module loading process happens principally through

the manipulation of environment variables like $PATH. There

is usually little or no data transfer involved.

The module loading process manipulates other special environment variables as well, including variables that influence where the system looks for software libraries, and sometimes variables which tell commercial software packages where to find license servers.

The module command also restores these shell environment variables to their previous state when a module is unloaded.

Software Versioning

So far, we’ve learned how to load and unload software packages. This is very useful. However, we have not yet addressed the issue of software versioning. At some point or other, you will run into issues where only one particular version of some software will be suitable. Perhaps a key bugfix only happened in a certain version, or version X broke compatibility with a file format you use. In either of these example cases, it helps to be very specific about what software is loaded.

Let’s examine the output of module avail more closely.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ module avail

---------------------- /cluster/modulefiles/all -------------------------

4ti2/1.6.9-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1 gmsh/4.5.6-foss-2019b-Python-3.7.4

ABySS/2.0.2-gompi-2019a gnuplot/5.2.6-GCCcore-8.2.0

AdapterRemoval/2.3.1-foss-2018b gnuplot/5.2.8-GCCcore-8.3.0

AdapterRemoval/2.3.1-GCC-8.2.0-2.31.1 Go/1.13.1

ADF/2019.103+StaticMKL gompi/2018b

AdmixTools/5.1-GCC-7.3.0-2.30 gompi/2019a

ADMIXTURE/1.3.0 gompi/2019b

[removed most of the output here for clarity]

----------------------- /cluster/modulefiles/external ---------------------

appusage/1.0 hpcx/2.4 hpcx/2.5 hpcx/2.6

Where:

S: Module is Sticky, requires --force to unload or purge

L: Module is loaded

Aliases: Aliases exist: foo/1.2.3 (1.2) means that "module load foo/1.2"

will load foo/1.2.3

Use "module spider" to find all possible modules.

Use "module keyword key1 key2 ..." to search for all possible modules matching

any of the "keys".

Let’s take a closer look at the gcc module. GCC is an extremely widely used

C/C++/Fortran compiler. Tons of software is dependent on the GCC version, and

might not compile or run if the wrong version is loaded. In this case, there

are few different versions:

GCC/7.3.0-2.30 GCC/8.2.0-2.31.1 GCC/8.3.0 GCC/9.3.0

How do we load each copy and which copy is the default?

On SAGA and Fram we do not have default modules and we must use the full name to load it.

module load gcc

Lmod has detected the following error: The following module(s) are unknown:

"gcc"

Please check the spelling or version number. Also try "module spider ..."

It is also possible your cache file is out-of-date; it may help to try:

$ module --ignore-cache load "gcc"

To load a software module we must specify the full module name:

module load GCC/8.2.0-2.31.1

gcc --version

Using Software Modules in Scripts

Create a job that is able to run

python3 --version. Remember, no software is loaded by default! Running a job is just like logging on to the system (you should not assume a module loaded on the login node is loaded on a compute node).Solution

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ nano python-module.sh [yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ cat python-module.sh#!/bin/bash module load python3 --version[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ sbatch --qos=<input_qos> python-module.sh

Key Points

Load software with

module load softwareName.Unload software with

module unloadThe module system handles software versioning and package conflicts for you automatically.

Transferring files with remote computers

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How do I transfer files to (and from) the cluster?

Objectives

Transfer files to and from a computing cluster.

Performing work on a remote computer is not very useful if we cannot get files to or from the cluster. There are several options for transferring data between computing resources using CLI and GUI utilities, a few of which we will cover.

Download Files From the Internet

One of the most straightforward ways to download files is to use either curl

or wget. One of these is usually installed in most Linux shells, on Mac OS

terminal and in GitBash. Any file that can be downloaded in your web browser

through a direct link can be downloaded using curl -O or wget. This is a

quick way to download datasets or source code.

The syntax for these commands is: curl -O https://some/link/to/a/file

and wget https://some/link/to/a/file. Try it out by downloading

some material we’ll use later on, from a terminal on your local machine.

[user@laptop ~]$ curl -O https://baskerville-hpc.github.io/hpc-intro/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

or

[user@laptop ~]$ wget https://baskerville-hpc.github.io/hpc-intro/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

tar.gz?This is an archive file format, just like

.zip, commonly used and supported by default on Linux, which is the operating system the majority of HPC cluster machines run. You may also see the extension.tgz, which is exactly the same. We’ll talk more about “tarballs,” since “tar-dot-g-z” is a mouthful, later on.

Transferring Single Files and Folders With scp

To copy a single file to or from the cluster, we can use scp (“secure copy”).

The syntax can be a little complex for new users, but we’ll break it down.

The scp command is a relative of the ssh command we used to

access the system, and can use the same public-key authentication

mechanism.

To upload to another computer:

[user@laptop ~]$ scp path/to/local/file.txt yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:/path/on/Baskerville

To download from another computer:

[user@laptop ~]$ scp yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:/path/on/Baskerville/file.txt path/to/local/

Note that everything after the : is relative to our home directory on the

remote computer. We can leave it at that if we don’t care where the file goes.

[user@laptop ~]$ scp local-file.txt yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:

Upload a File

Copy the file you just downloaded from the Internet to your home directory on Baskerville.

Solution

[user@laptop ~]$ scp hpc-intro-data.tar.gz yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:~/

Most computer clusters are protected from the open internet by a firewall.

This means that the curl command will fail, as an address outside the

firewall is unreachable from the inside. To get around this, run the curl or

wget command from your local machine to download the file, then use the scp

command to upload it to the cluster.

Why Not Download on Baskerville Directly?

Try downloading the file directly. Note that it may well fail, and that’s OK!

Commands

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk [yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ curl -O https://baskerville-hpc.github.io/hpc-intro/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gz or [yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ wget https://baskerville-hpc.github.io/hpc-intro/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gzDid it work? If not, what does the terminal output tell you about what happened?

To copy a whole directory, we add the -r flag, for “recursive”: copy the

item specified, and every item below it, and every item below those… until it

reaches the bottom of the directory tree rooted at the folder name you

provided.

[user@laptop ~]$ scp -r some-local-folder yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:target-directory/

Caution

For a large directory – either in size or number of files – copying with

-rcan take a long time to complete.

What’s in a /?

When using scp, you may have noticed that a : always follows the remote

computer name; sometimes a / follows that, and sometimes not, and sometimes

there’s a final /. On Linux computers, / is the root directory, the

location where the entire filesystem (and others attached to it) is anchored. A

path starting with a / is called absolute, since there can be nothing above

the root /. A path that does not start with / is called relative, since

it is not anchored to the root.

If you want to upload a file to a location inside your home directory –

which is often the case – then you don’t need a leading /. After the

:, start writing the sequence of folders that lead to the final storage

location for the file or, as mentioned above, provide nothing if your home

directory is the destination.

A trailing slash on the target directory is optional, and has no effect for

scp -r, but is important in other commands, like rsync.

A Note on

rsyncAs you gain experience with transferring files, you may find the

scpcommand limiting. The rsync utility provides advanced features for file transfer and is typically faster compared to bothscpandsftp(see below). It is especially useful for transferring large and/or many files and creating synced backup folders.The syntax is similar to

scp. To transfer to another computer with commonly used options:[user@laptop ~]$ rsync -avzP path/to/local/file.txt yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:directory/path/on/Baskerville/The options are:

a(archive) to preserve file timestamps and permissions among other thingsv(verbose) to get verbose output to help monitor the transferz(compression) to compress the file during transit to reduce size and transfer timeP(partial/progress) to preserve partially transferred files in case of an interruption and also displays the progress of the transfer.To recursively copy a directory, we can use the same options:

[user@laptop ~]$ rsync -avzP path/to/local/dir yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:directory/path/on/Baskerville/As written, this will place the local directory and its contents under the specified directory on the remote system. If the trailing slash is omitted on the destination, a new directory corresponding to the transferred directory (‘dir’ in the example) will not be created, and the contents of the source directory will be copied directly into the destination directory.

The

a(archive) option implies recursion.To download a file, we simply change the source and destination:

[user@laptop ~]$ rsync -avzP yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:path/on/Baskerville/file.txt path/to/local/

All file transfers using the above methods use SSH to encrypt data sent through

the network. So, if you can connect via SSH, you will be able to transfer

files. By default, SSH uses network port 22. If a custom SSH port is in use,

you will have to specify it using the appropriate flag, often -p, -P, or

--port. Check --help or the man page if you’re unsure.

Change the Rsync Port

Say we have to connect

rsyncthrough port 768 instead of 22. How would we modify this command?[user@laptop ~]$ rsync test.txt yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:Solution

[user@laptop ~]$ rsync --help | grep port --port=PORT specify double-colon alternate port number See http://rsync.samba.org/ for updates, bug reports, and answers [user@laptop ~]$ rsync --port=768 test.txt yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk:

Transferring Files Interactively with FileZilla

FileZilla is a cross-platform client for downloading and uploading files to and

from a remote computer. It is absolutely fool-proof and always works quite

well. It uses the sftp protocol. You can read more about using the sftp

protocol in the command line in the

lesson discussion.

Download and install the FileZilla client from https://filezilla-project.org. After installing and opening the program, you should end up with a window with a file browser of your local system on the left hand side of the screen. When you connect to the cluster, your cluster files will appear on the right hand side.

To connect to the cluster, we’ll just need to enter our credentials at the top of the screen:

- Host:

sftp://login.baskerville.ac.uk - User: Your cluster username

- Password: Your cluster password

- Port: (leave blank to use the default port)

Hit “Quickconnect” to connect. You should see your remote files appear on the right hand side of the screen. You can drag-and-drop files between the left (local) and right (remote) sides of the screen to transfer files.

Finally, if you need to move large files (typically larger than a gigabyte)

from one remote computer to another remote computer, SSH in to the computer

hosting the files and use scp or rsync to transfer over to the other. This

will be more efficient than using FileZilla (or related applications) that

would copy from the source to your local machine, then to the destination

machine.

Archiving Files

One of the biggest challenges we often face when transferring data between remote HPC systems is that of large numbers of files. There is an overhead to transferring each individual file and when we are transferring large numbers of files these overheads combine to slow down our transfers to a large degree.

The solution to this problem is to archive multiple files into smaller numbers of larger files before we transfer the data to improve our transfer efficiency. Sometimes we will combine archiving with compression to reduce the amount of data we have to transfer and so speed up the transfer.

The most common archiving command you will use on a (Linux) HPC cluster is

tar. tar can be used to combine files into a single archive file and,

optionally, compress it.

Let’s start with the file we downloaded from the lesson site,

hpc-lesson-data.tar.gz. The “gz” part stands for gzip, which is a

compression library. Reading this file name, it appears somebody took a folder

named “hpc-lesson-data,” wrapped up all its contents in a single file with

tar, then compressed that archive with gzip to save space. Let’s check

using tar with the -t flag, which prints the “table of contents”

without unpacking the file, specified by -f <filename>, on the remote

computer. Note that you can concatenate the two flags, instead of writing

-t -f separately.

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.baskerville.ac.uk

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ tar -tf hpc-lesson-data.tar.gz

hpc-intro-data/

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01971Z.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goostats

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goodiff

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02018B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01736A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01812A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040Z.txt

This shows a folder containing another folder, which contains a bunch of files.

If you’ve taken The Carpentries’ Shell lesson recently, these might look

familiar. Let’s see about that compression, using du for “disk

usage”.

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ du -sh hpc-lesson-data.tar.gz

36K hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

Files Occupy at Least One “Block”

If the filesystem block size is larger than 36 KB, you’ll see a larger number: files cannot be smaller than one block.

Now let’s unpack the archive. We’ll run tar with a few common flags:

-xto extract the archive-vfor verbose output-zfor gzip compression-ffor the file to be unpacked

When it’s done, check the directory size with du and compare.

Extract the Archive

Using the four flags above, unpack the lesson data using

tar. Then, check the size of the whole unpacked directory usingdu.Hint:

tarlets you concatenate flags.Commands

[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ tar -xvzf hpc-lesson-data.tar.gzhpc-intro-data/ hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/ hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01971Z.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goostats hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goodiff hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02018B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01736A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01812A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040Z.txtNote that we did not type out

-x -v -z -f, thanks to the flag concatenation, though the command works identically either way.[yourUsername@bask-pg0310u18a ~]$ du -sh hpc-lesson-data 144K hpc-intro-dataWas the Data Compressed?

Text files compress nicely: the “tarball” is one-quarter the total size of the raw data!

If you want to reverse the process – compressing raw data instead of

extracting it – set a c flag instead of x, set the archive filename,

then provide a directory to compress:

[user@laptop ~]$ tar -cvzf compressed_data.tar.gz hpc-intro-data

Working with Windows

When you transfer text files to from a Windows system to a Unix system (Mac, Linux, BSD, Solaris, etc.) this can cause problems. Windows encodes its files slightly different than Unix, and adds an extra character to every line.

On a Unix system, every line in a file ends with a

\n(newline). On Windows, every line in a file ends with a\r\n(carriage return + newline). This causes problems sometimes.Though most modern programming languages and software handles this correctly, in some rare instances, you may run into an issue. The solution is to convert a file from Windows to Unix encoding with the

dos2unixcommand.You can identify if a file has Windows line endings with

cat -A filename. A file with Windows line endings will have^M$at the end of every line. A file with Unix line endings will have$at the end of a line.To convert the file, just run

dos2unix filename. (Conversely, to convert back to Windows format, you can rununix2dos filename.)

Key Points

wgetandcurl -Odownload a file from the internet.

scpandrsynctransfer files to and from your computer.You can use an SFTP client like FileZilla to transfer files through a GUI.

Running a parallel job

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 60 minQuestions

How do we execute a task in parallel?

What benefits arise from parallel execution?

What are the limits of gains from execution in parallel?

Objectives

Construct a program that can execute in parallel.

Prepare a job submission script for the parallel executable.

Launch jobs with parallel execution.

Record and summarize the timing and accuracy of jobs.

Describe the relationship between job parallelism and performance.

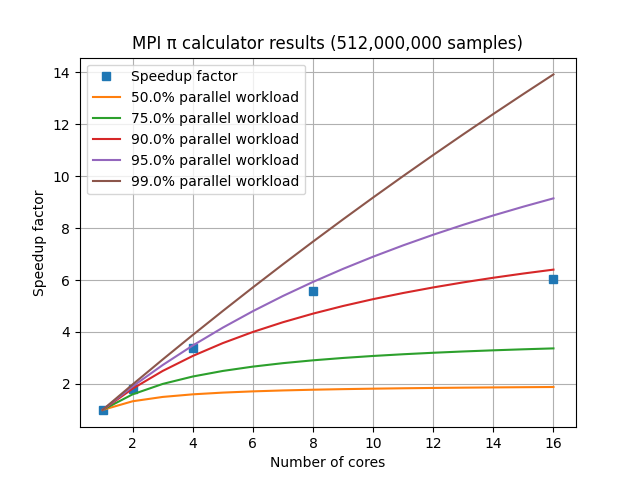

We now have the tools we need to run a multi-processor job. This is a very important aspect of HPC systems, as parallelism is one of the primary tools we have to improve the performance of computational tasks.

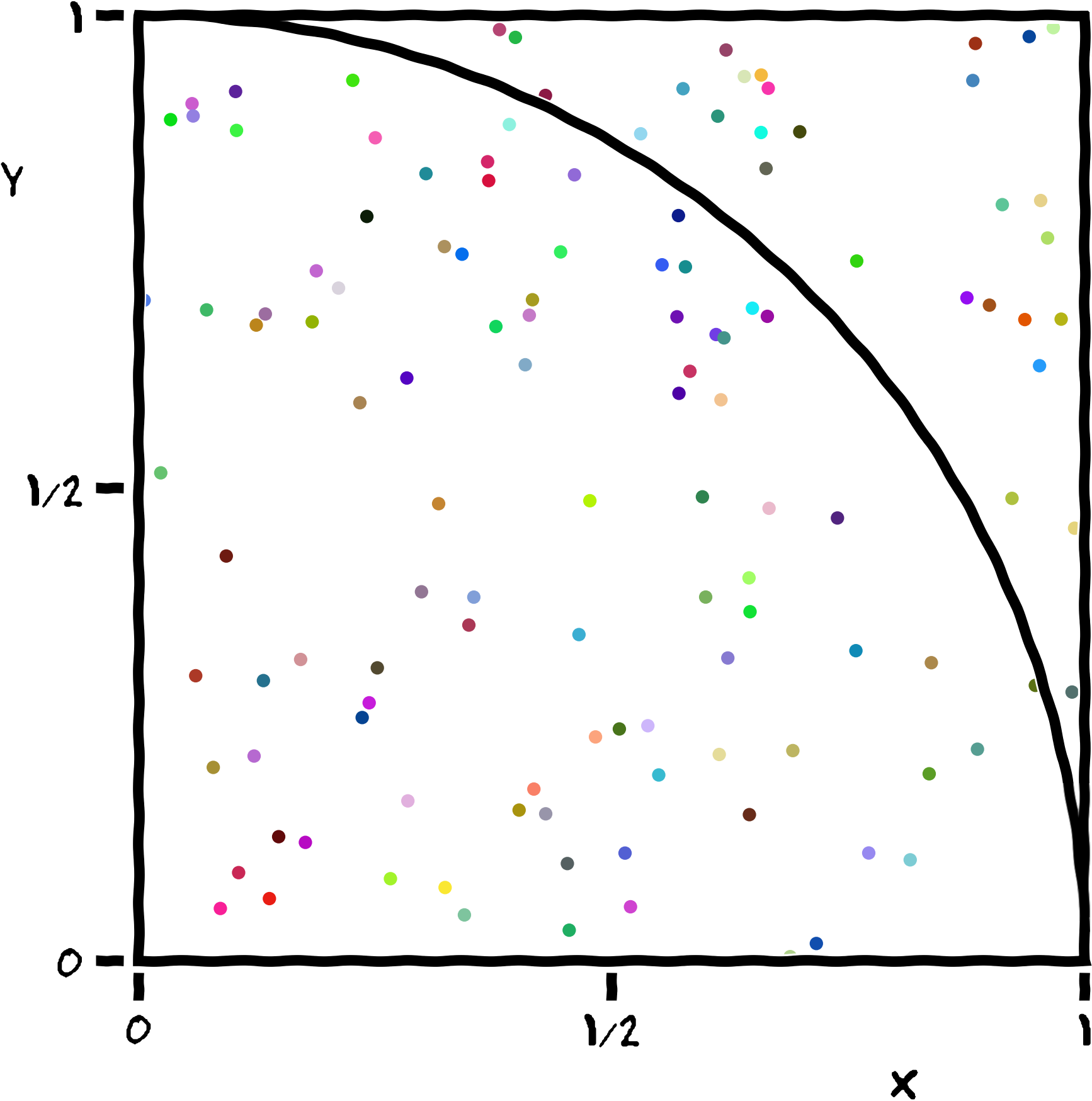

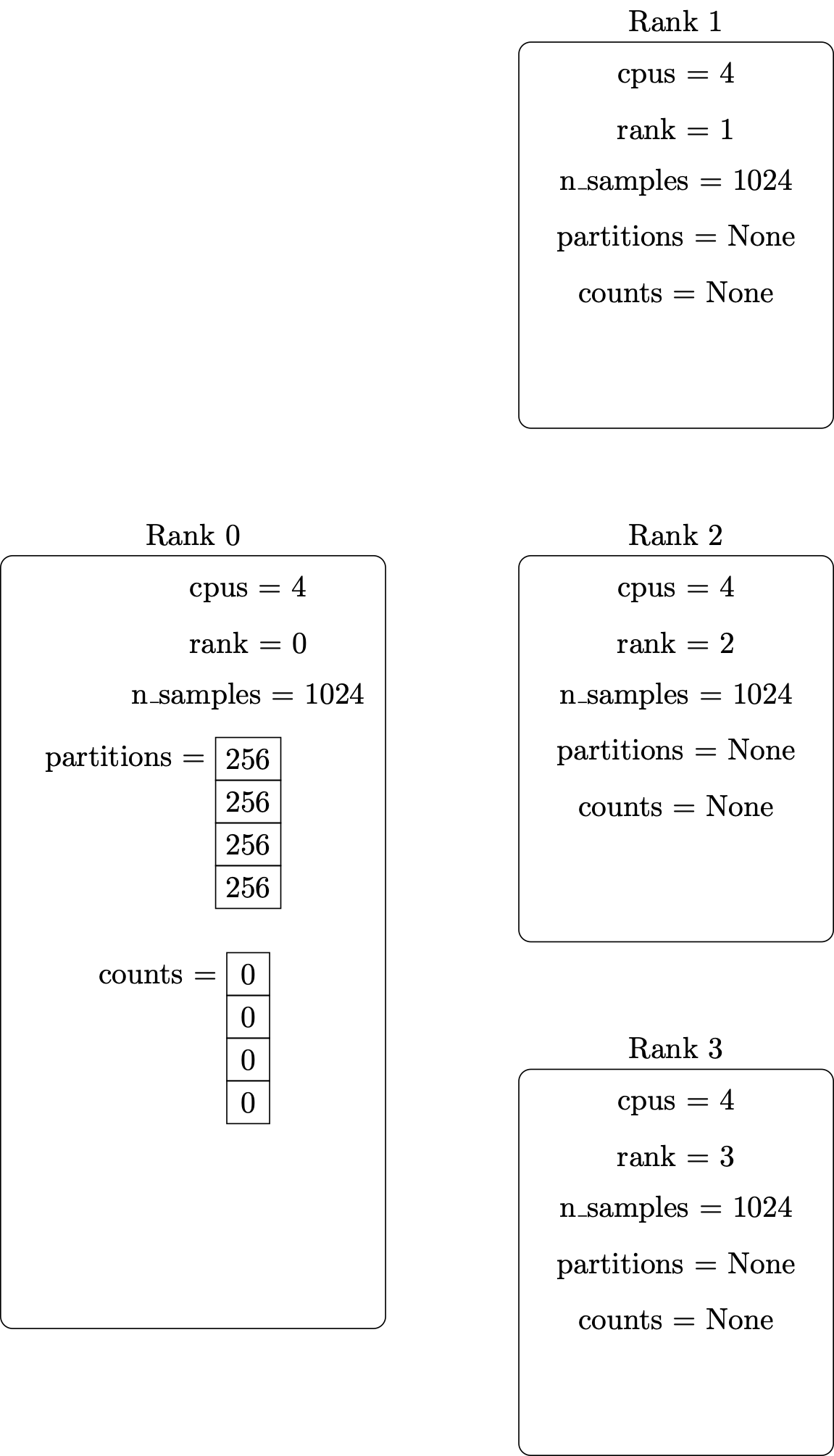

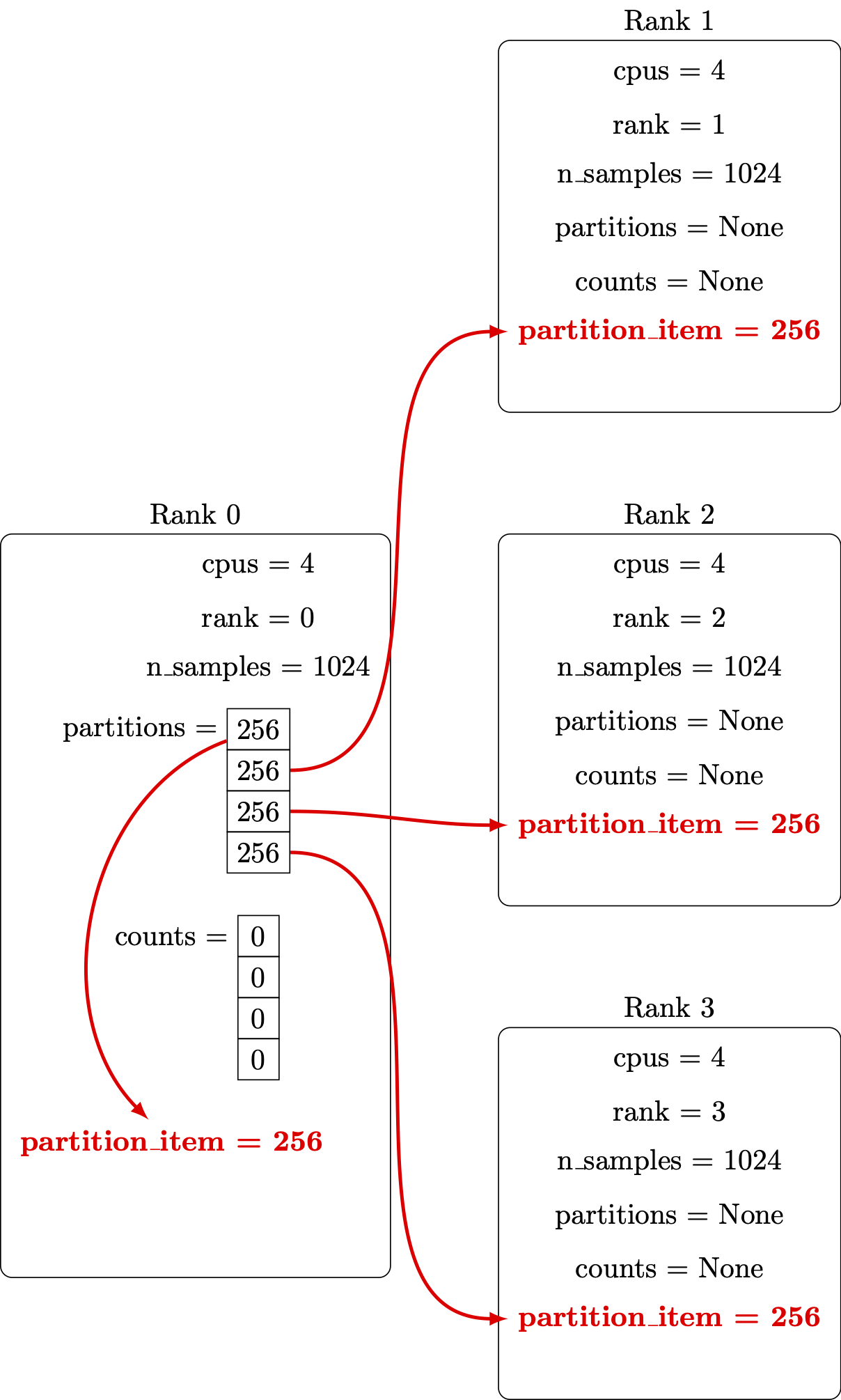

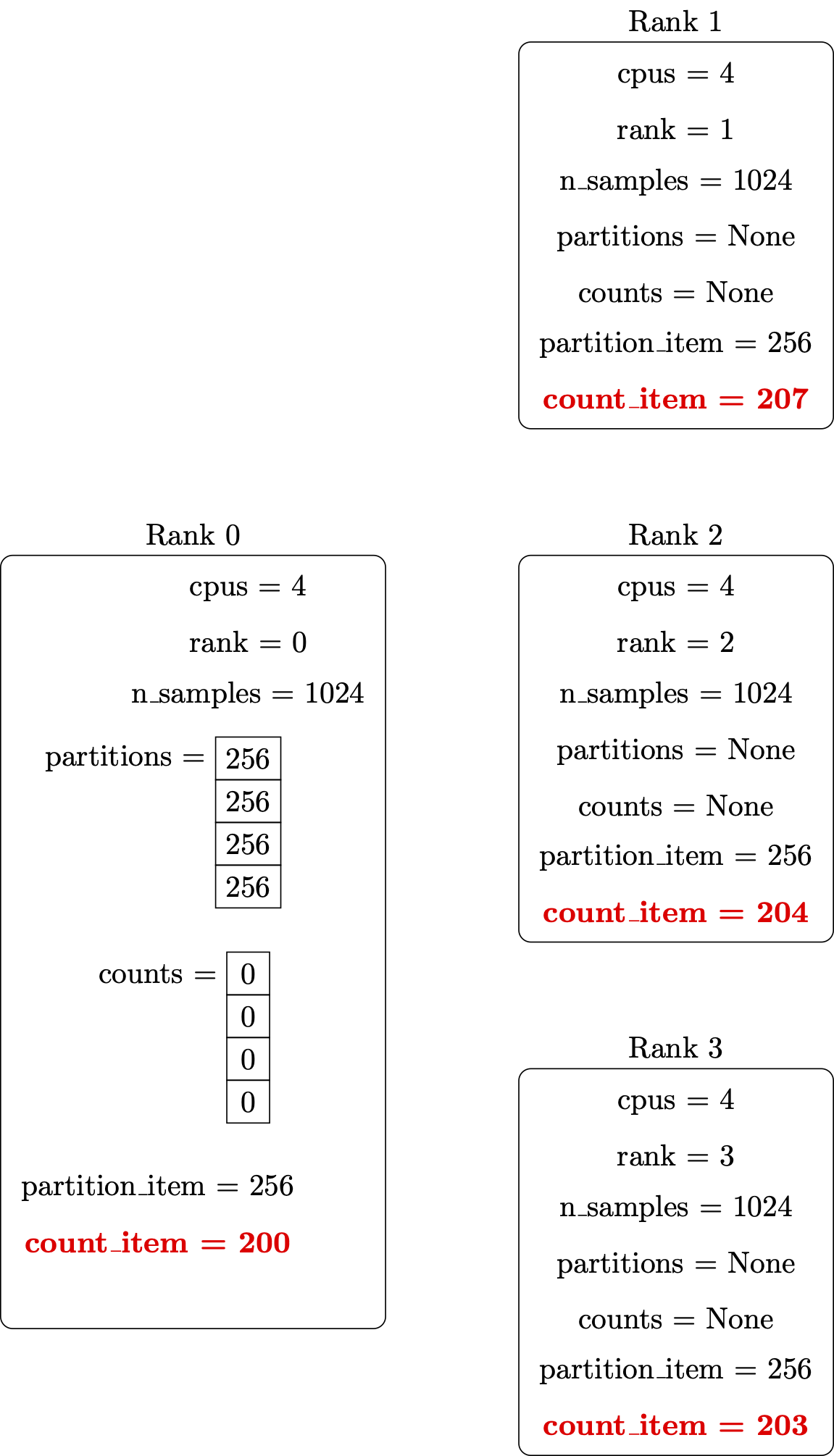

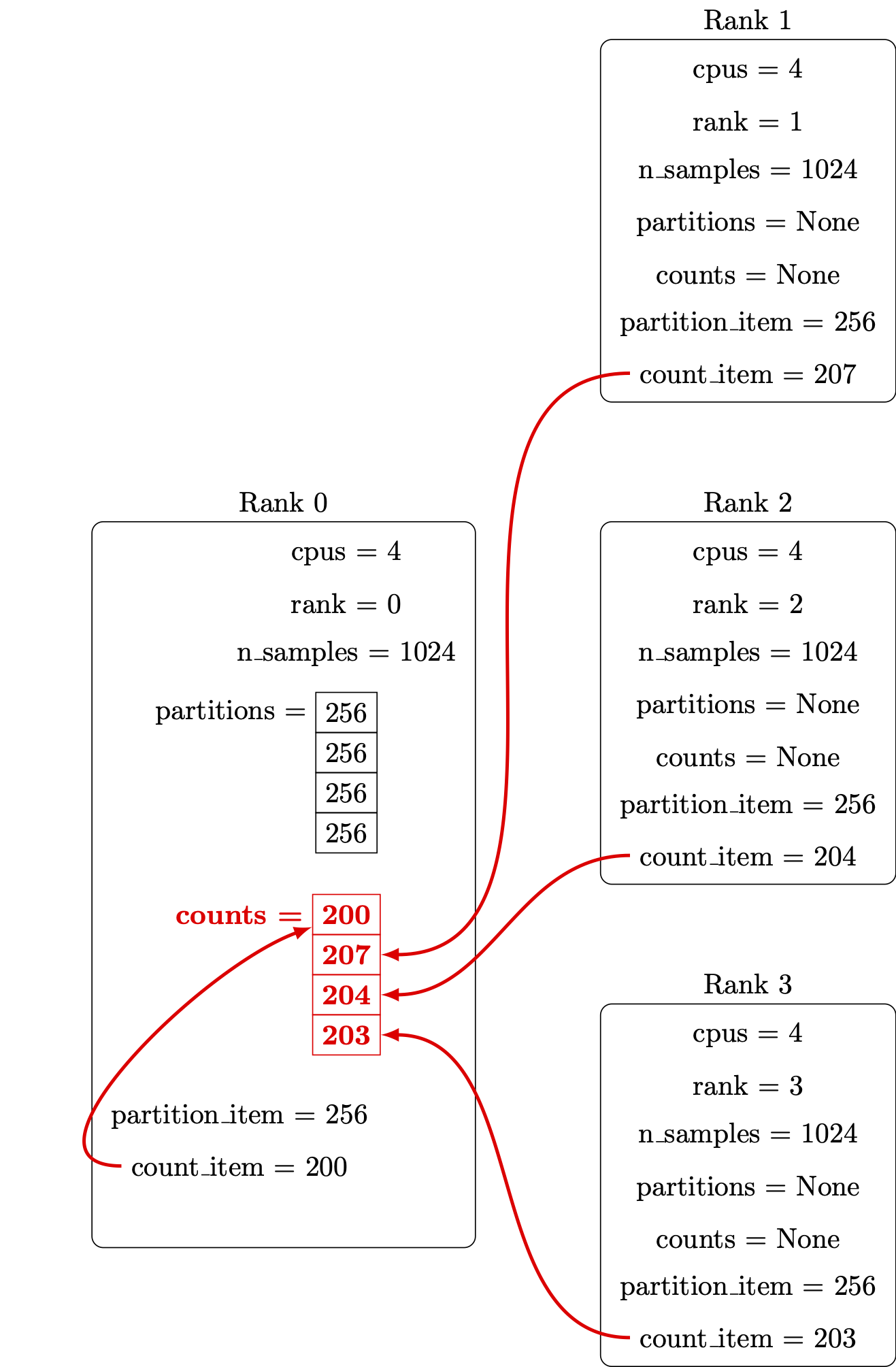

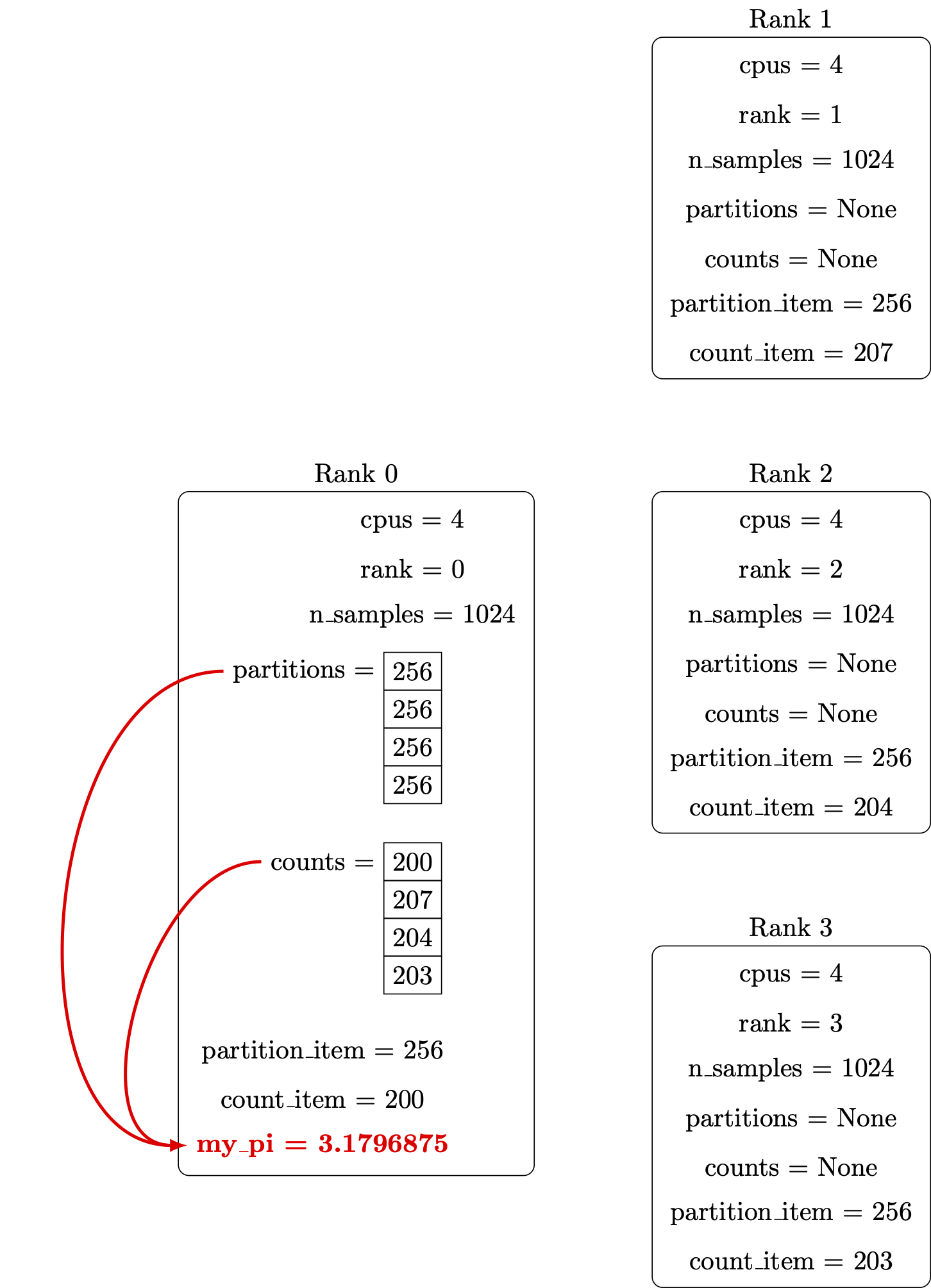

Our example implements a stochastic algorithm for estimating the value of π, the ratio of the circumference to the diameter of a circle. The program generates a large number of random points on a 1×1 square centered on (½,½), and checks how many of these points fall inside the unit circle. On average, π/4 of the randomly-selected points should fall in the circle, so π can be estimated from 4f, where f is the observed fraction of points that fall in the circle. Because each sample is independent, this algorithm is easily implemented in parallel.

A Serial Solution to the Problem

We start from a Python script using concepts taught in Software Carpentry’s Programming with Python workshops. We want to allow the user to specify how many random points should be used to calculate π through a command-line parameter. This script will only use a single CPU for its entire run, so it’s classified as a serial process.

Let’s write a Python program, pi.py, to estimate π for us.

Start by importing the numpy module for calculating the results,

and the sys module to process command-line parameters:

import numpy as np

import sys

We define a Python function inside_circle that accepts a single parameter

for the number of random points used to calculate π.

See Programming with Python: Creating Functions

for a review of Python functions.

It randomly samples points with both x and y on the half-open interval

[0, 1).

It then computes their distances from the origin (i.e., radii), and returns

how many of those distances were less than or equal to 1.0.

All of this is done using vectors of double-precision (64-bit)

floating-point values.

def inside_circle(total_count):

x = np.random.uniform(size=total_count)

y = np.random.uniform(size=total_count)

radii = np.sqrt(x * x + y * y)

count = len(radii[np.where(radii<=1.0)])

return count

Next, we create a main function to call the inside_circle function and

calculate π from its returned result.

See Programming with Python: Command-Line Programs

for a review of main functions and parsing command-line parameters.

def main():

n_samples = int(sys.argv[1])

counts = inside_circle(n_samples)

my_pi = 4.0 * counts / n_samples

print(my_pi)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

If we run the Python script locally with a command-line parameter, as in

python pi-serial.py 1024, we should see the script print its estimate of

π:

[user@laptop ~]$ python pi-serial.py 1024

3.10546875

Random Number Generation

In the preceding code, random numbers are conveniently generated using the built-in capabilities of NumPy. In general, random-number generation is difficult to do well, it’s easy to accidentally introduce correlations into the generated sequence.

- Discuss why generating high quality random numbers might be difficult.

- Is the quality of random numbers generated sufficient for estimating π in this implementation?

Solution

- Computers are deterministic and produce pseudo random numbers using an algorithm. The choice of algorithm and its parameters determines how random the generated numbers are. Pseudo random number generation algorithms usually produce a sequence numbers taking the previous output as an input for generating the next number. At some point the sequence of pseudo random numbers will repeat, so care is required to make sure the repetition period is long and that the generated numbers have statistical properties similar to those of true random numbers.

- Yes.

Measuring Performance of the Serial Solution

The stochastic method used to estimate π should converge on the true

value as the number of random points increases.

But as the number of points increases, creating the variables x, y, and

radii requires more time and more memory.

Eventually, the memory required may exceed what’s available on our local

laptop or desktop, or the time required may be too long to meet a deadline.

So we’d like to take some measurements of how much memory and time the script

requires, and later take the same measurements after creating a parallel